Vol. 6 / 2018.11.02

JUICE Player Interviews

JUICE and Prior Projects

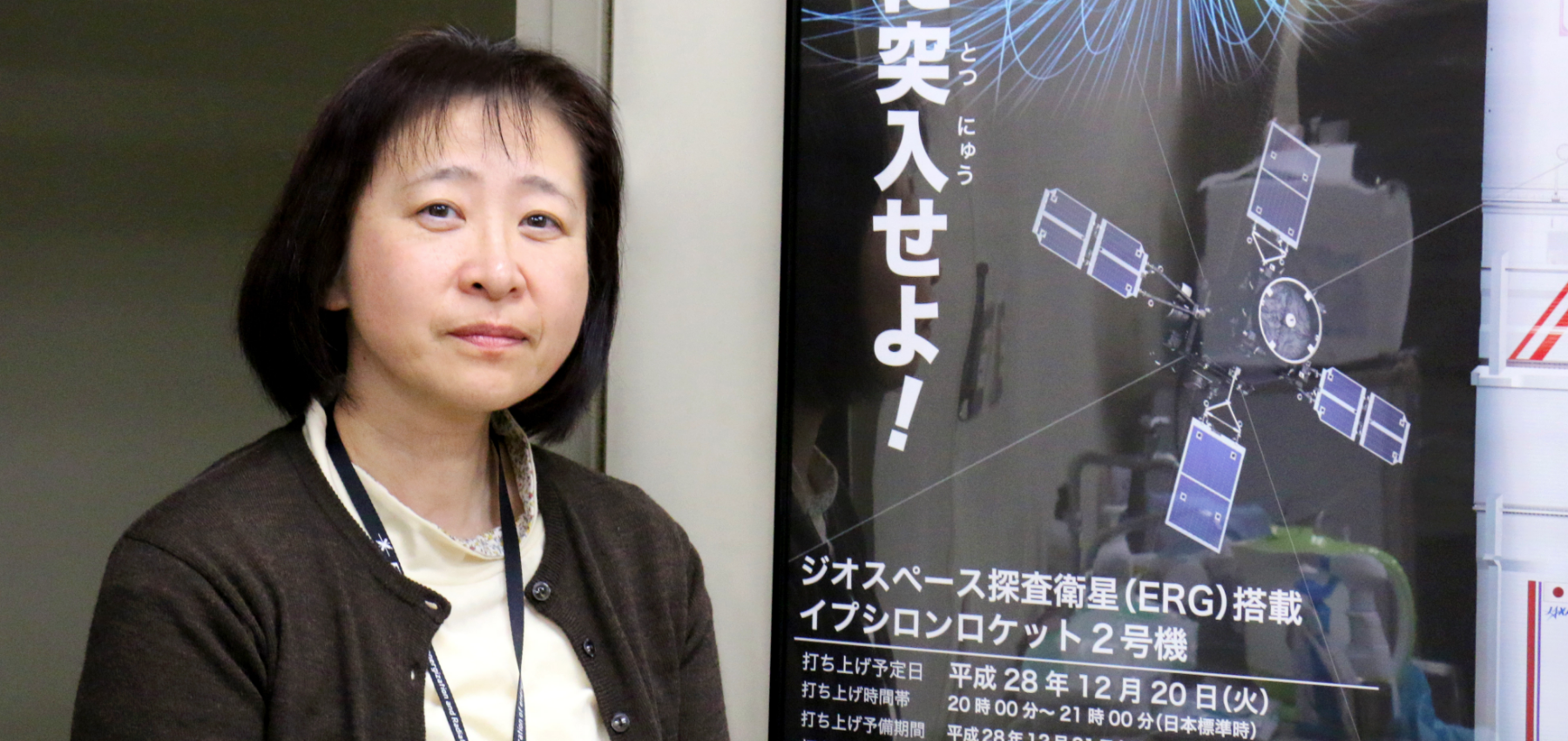

——The fifth interview is with JUICE JAPAN Pre-Project Manager Professor Ayako Matsuoka of the Institute of Space and Astronautical Science. (As of 2018)

-What projects are you currently involved in?

Dr. Matsuoka: Right now, I am involved in three projects: Arase, which is an investigation of geospace, MIO (BepiColombo) on Mercury, and JUICE, which is investigating Jupiter.

——Please can you tell us about your roles in Arase and MIO?

Dr. Matsuoka:

With Arase, I am working as the PI (Principal Investigator) on the magnetic field observation instrumentation, which is one of the nine types of scientific observation equipment to be installed. Arase was launched in December 2016, and, thankfully, it is now gathering data very smoothly. This data is primarily being used for studying the radiation belt, organizing the themes that can be researched by team members, and preparing the data to be used for those themes, for example. We are in an enjoyable period where we can use this data when writing essays and producing results.

MIO’s launch is in October 2018, and so we are now enjoying working on the final preparations. You can see the details on the MMO Project Site just as you can with the JUICE Project Site.

Projects that have made an impact and learnings from those projects

——Have there been any projects that have made a particular impact on you?

Dr. Matsuoka:

All of them have made an impact, but, more than the results, in terms of past experiences leading up to the present, and the project with the greatest learnings and useful outcomes, it has to be the Nozomi Mars explorer, which was launched in 1998.

My time as a student was spent during the era of Akebono and GEOTAIL, and my role as a student was to analyze the data, whereas with the Nozomi Mars explorer, I was involved in the instruments for measuring the magnetic field for the first time.

Unfortunately, Nozomi was not able to reach orbit around Mars, and it became known as a failure as a result, but I learned many important things that I have put to use in later developments in my work centering on magnetic field measurement instrumentation, and Nozomi was a project that hugely contributed to that.

——I’m sure that you learnt a lot from the process, but was there something in specific that was invigorating and useful?

Dr. Matsuoka: Matsuoka : With the know-how from making the 5m mast (arm) for the Nozomi Mars explorer, it was possible to later use the same mast for Arase, when there was no budget or time for development. Nozomi was launched exactly 20 years ago, in 1998, but we were perfectly able to make use of the mast that we had designed with the manufacturer for Arase, which I was very glad about.

——It’s amazing that the latest designs from that period could still be used in the latest designs of today.

Background to Participation in JUICE

——Was the request for your participation in JUICE due to the fact that Nozomi was actually a successful experiment?

Dr. Matsuoka: That’s right. That development is certainly connected to JUICE. Japan, the UK, Germany and Austria are cooperating on the JUICE instruments for measuring magnetic fields, but the background to my participation in JUICE is that the mast was requested from Japan by Michele Dougherty from Imperial College in the UK, who is the PI for the magnetic field observation equipment. The masts for Nozomi, Arase and MIO were 5m but, for the Kaguya lunar orbiter, a 12m mast was successfully made.

Making Even Better Equipment

——Because of the size of the probe, the parts have to be quite long. What exactly is the purpose of the mast?

Dr. Matsuoka:

Various instruments are equipped on man-made satellites, but if the instruments for observing the magnetic field are placed on the surface of the satellite, the magnetic field emitted by the satellite itself will cause interference, and the natural magnetic field that we want to observe will not be measurable. Therefore, the arms used on man-made satellites should be as long as possible, with the sensors placed at the tip of the arm, because we want to get as close as possible to the natural magnetic field. That long arm is the mast.

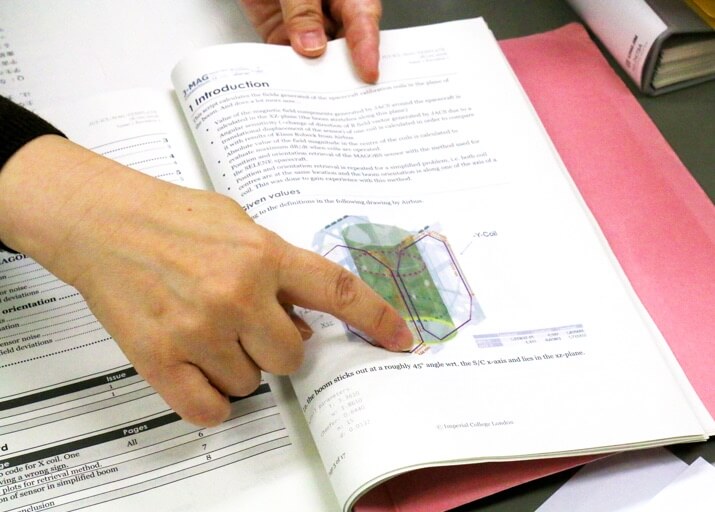

The 8m mast that was required was requested from Japan, which has experience in such experiments. The boom has to extend correctly without bending, which is difficult with a folding boom. However, the decision to produce an 8m boom in Spain was made by ESA.

We are now working on making the angle of the boom precise in order to clarify the position of the magnetic field measuring sensor in space.

——What kind of angle is required?

Dr. Matsuoka: 0.16 degrees.

——0.16 degrees…Is it possible to make such precise adjustments in space?

This must be a really big problem with many challenges, such as the kind of magnetic field that will be generated in terms of the precision of the angle.

Dr. Matsuoka:

At present,numerous proposals have already been made to the UK. Wide-ranging measurements have been carried out, such as the time intervals for turning the electricity on and off and the strength of the electric current, and the results are being discussed. It is important that we talk with all of the engineers in the UK that are in charge of the magnetic field observation equipment as a whole rather than just with the members of the magnetic field observation instruments because it will not be possible to produce the equipment if the manufacturer of the satellite does not give its approval.

Unless the positioning of the producer is understood, unreasonable demands might be made. In Japan, as we also have experience in manufacturing, our requests have been made while taking measures and considering how to enable that was thought to be impossible, and both the engineers and the PI were delighted with the results of the proposal made in autumn 2017. I was relieved when we were asked to take charge of tests after production and the tests to ensure correct functionality after launch, which is something I’m looking forward to.

Communication in Japan and Internationally

Dr. Matsuoka:

Currently, although almost all of the interaction is international, and there is almost no interaction with Japanese members, I would like to see more Japanese members. At the moment, I am working on calculations and designs rather than doing work that can be handed down, so, in practice, I am working alone.

Nevertheless, I don’t feel isolated at all, and the members from Germany and Austria who I am actually working with right now are also from MIO, while the PI in the UK is someone I have known since I spent about one year at Imperial College about 22 years ago. I never thought that we would be working together on a project in the future! It’s easy to work together because we know each other’s dispositions. If Japan alone was responsible for the project, it would proceed in a different way because Europeans and others have different national characteristics, so there is a strong feeling of international cooperation.

——In terms of the way of working, are there some differences that you feel more clearly?

Dr. Matsuoka:

I am currently working with Germany and Austria on MIO, and they are highly efficient in doing precisely what has been agreed on the basis of principles of rationality and efficiency. One of the differences is that, rather than feeling anxious and keeping quiet, like Japanese people, work moves forward with clearly defined categories of responsibility.

If all of the work is divided, for example, with some people working on the project, others on production, and others on analysis, then people who are producing things will be absorbed by production, and managers will be absorbed with management. Of course, there has to be some level of understanding of the jobs of other people, and engineers will always try to do something even if it is not easy. Things that are almost impossible have been achieved.

——There’s a strong relationship of trust between researchers with their high ideals and superior engineers who are able to freely show their abilities.

Childhood background to taking an interest in space

——From speaking to you, it seems that you have a rich vocabulary. Did you ever think about working in the humanities?

Dr. Matsuoka:I like both, but when I was a student I thought it was interesting that physical things can be expressed using mathematical techniques, and that’s when I realized that physics was fun.

——I think there were few women of your generation who took up physics, but what was the deciding factor in taking this route?

Dr. Matsuoka:

When I was selecting a university, for example, although I looked at the booklets to find out whether I would be able to do something related to space, I ended up thinking that it is okay as long as I can do physics. When I was deciding between the science department and the engineering department, I really wanted to be able to use formulae to explain natural phenomena, so I went with the science department.

Although I was studying in the science department, I found out that I could study space in the Department of Earth and Planetary Physics. There were barriers to moving into the field of space, and it felt like something remote, so I didn’t make the move at that time.

When I was in the second year of my Master’s degree, I started to look for employment in areas unrelated to space either in a company, or at a government research agency, and finally, on the day when I had to decide, I somehow couldn’t imagine myself doing research or working in those places. I don’t know why. I had been worrying about it until the day before, and, in the end, I still wanted to study, so I moved into a doctoral course. Until that time, it didn’t seem real that I could move into a space-related area. It was only at that point that I understood that what I wanted to do was space research.

Enjoying research and work

——What do you think are the important and enjoyable things about working?

Dr. Matsuoka:

Until I started working, I thought that researchers were more contained, and that they only had connections with other researchers, but we have close discussions with people from so many different fields, not only manufacturers and researchers, so I think that communication is important.

What has really moved me and made an impact was of course the pre-launch preparations, but my heart was also racing when the first data came in after the launch. Also, we only understood the direction of magnetic fields in outer space after looking more closely at the data, so my heart was pounding at that time as well. It’s like I’ve been wishing for success despite the worry as I made sure of each and every step.

——Listening to this story, these are heartwarming thoughts, and you have the look of a “parent” who continues to watch over the activity after giving birth to, raising, and then becoming independent from a child. How do you feel about handing over the project to the next generation?

JUICE Connects to the Next Generation

Dr. Matsuoka:

Hmm… I want to keep on carefully watching over the activity. And I want the next generation of people who are involved to include more people who can handle the data. Planetary missions are always going to involve long distances and periods of time, so the team involved in preparation and analysis will change.

I have also been involved in BepiColombo since about the year 2000, but it won’t arrive at Mercury until 2025. When JUICE arrives at Ganymede, I will no longer be a researcher, but it is already clear that this is a project that will leave behind something good for future generations, and in order for Japan to be taking the lead at that time, I want to make sure that I do whatever I can for Japan right now.

For that reason, we have to put in a lot of effort in the early stages of JUICE. We have to do things that will lead to trust being built in other Japanese researchers, and in Japan as a country.

——Although it is difficult, for the sake of the future of science, and for the sake of the future of Japan, please continue working with your considerate perspectives.

Interviewed by Nishikawa, Nyan & Co.